Part One – why it is (probably) happening

Part One – why it is (probably) happening

Brexit hasn’t happened yet. 18 months on from the referendum, the British are hardly any clearer about what their country and their lives will be like after it leaves the EU; and this despite the fact that every single day, something to do with Brexit dominates the serious news channels.

At the very least, it has become clearer to many who voted for Brexit that the process of leaving the EU is far more complex than their political leaders had claimed. I doubt that on the day of the referendum more than 5% of the population could correctly state what Euratom is, or that the European Court of Human Rights is not an EU institution. Well, now they are finding these things out. Drip, drip, drip…the truth about Brexit comes out in little drips.

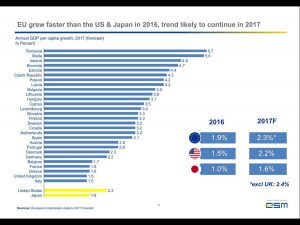

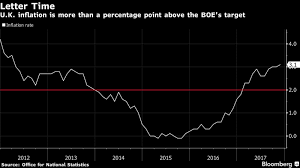

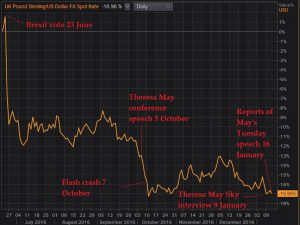

Then there is the economy. In the referendum campaign, some Remain politicians appeared to suggest that there would be an immediate economic disaster, the day after the vote to leave. This was a very foolish thing to suggest. Unless there is a nuclear strike or something similar, the 6th biggest economy in the world cannot go into recession overnight (indeed, 6 months is the minimum period before a recession can actually be officially declared). But during 2017, the problems have started to become apparent. Sterling (£) dropped against all major currencies straight away, which has resulted in inflation running at 3%, and now GDP growing at a much slower rate than in the EU as a whole. So even before actually leaving the EU the decision means people are poorer (because wages are not keeping pace with inflation) and public services will be cut,(as the unexpectedly lower growth means lower tax revenues.

So why did the UK inflict this damage on itself?

18 months on it is easier to understand the answer as part of a wider global pattern which explains Trump, and populist political success in Europe, including here in CZ. Ordinary people suffered the results of the financial crash in 2008, and they have not seen a return of good times. We may say that in CEE, many people have never experienced the good times they expected after the fall of Communism. They look for easy answers, someone or something to blame. “The EU” is an easy target, especially when populist politicians encourage them to think it is the problem.

In truth, in most countries, most of the things which bother most people are entirely the responsibility of national politicians. Give yourself this little test: think of the three things in daily life which most vex you, which politicians can influence.

In the case of my sister in the UK the answers tended to be:

- the state of the National Health Service

- the apparent expensiveness of everything

- the poor state of public transport

But for many people, even if they listed those things, they also wanted to list something else. A factor that in their minds, caused these problems:

Immigration.

The NHS, they say, cannot cope because there are too many immigrants. Housing costs are pushed up by immigrants. Public transport is overcrowded because of immigrants. And immigrants bring lots of other terrible things . This message was actually the campaign message of the UK Independence Party whose leader, Nigel Farage, takes credit for Brexit, even though his party has only one MP in the Parliament of 620 seats (and that MP has since left the party).

In vain did more sensible voices point out that immigrants are actually providing the staff for the NHS, and other public services, that they tend to be younger, so they work hard, pay taxes and need less healthcare. And more than half the immigrants arriving each year were from outside the EU.

But I must admit that overall the UK has experienced a population increase not felt by any other EU country. When I left the UK in 1993, the population was 54million. Now it is 65 million. And of course the UK is not a big place. No wonder the health service, the transport system, and just about all public services, are struggling to cope. Furthermore immigrants tend to stick together. It was inevitable that British families could in some places find that their kids were outnumbered in school class by Polish kids. Successive British governments oversaw this increase in population but did nothing to plan for it.

The other problem was that it was and remains difficult to summarise why EU membership is a good thing – especially if it is necessary to do so in short emotive slogans. The pro-EU arguments are complex and quite sophisticated. They tended to be understood best by well-educated, well – travelled, people. Those who voted Brexit tended to be older and less well-educated. The Brexit voter demographic resembles that of voters for Trump and populist parties, including those of the SPD and to some extent ANO in CZ.

The result has proved extremely divisive. There are many stories of families, even partners who are permanently divided because of the way each person voted. My family is a case in point. My sister and her family all voted Remain. Her son was always a “Remain ultra” whereas she took her time to try and understand the issues. As a family they are not well off and neither she nor her husband went to University. But her husband is of immigrant background. My brother is a rampant Brexiteer. Everything is the fault of too many immigrants, and the liberal metropolitan elite. He classes me as one of that elite, who got “a slap in the face” from the referendum vote. How I am a member of that elite, and he is not, when we are two brothers, he has never explained. Nor has he commented on the rich irony that he has just married a Brazilian lady for whom he has paid a lot of money for her visa. My Mum, who passed away in August, broke my heart. After my Dad passed away in 1996, she retreated into a life where she got her news from the Daily Mail and talkshow radio. When I asked her a month later why she had voted Brexit, she said, angrily “Well..because They are making rules for us, and we cannot stop them” So I asked her, “can you give me an example of one of those rules, which has affected your daily life?” “No, not right now” she replied, again angrily. I reminded her that she had a Czech daughter in law, a Romanian neighbour, and a Polish cleaning girl who always brought her a Christmas present. What would they think, I asked her, if they knew you voted Brexit? She just stared at me, her brain visibly trying and failing to work out the connection. My Mum was one of the angry Brexiteers, but to this day, I do not know what she had to be angry about. Compared with many older people, her life to the end was comfortable, with family all around her. She was never angry with life in that way when my Dad was alive. I honestly believe the Daily Mail poisoned her mind.

What happens next?

Now, slowly, the opinion polls are suggesting that some people are regretting voting Brexit.  It is not yet a big margin, but the trend starts to look clear. And this is surely because now, only now, drip, drip, drip, people are working out what leaving the EU will mean for the UK and for them. That in turn shows us that this was never a question that could sensibly be decided by a referendum. Few people understood the issues sufficiently. Only now is it clear that there are several possible forms of Brexit, with many other issues to be negotiated individually. We don’t yet know if the UK will agree to stay within the Single Market and/or the Customs Union. Once that becomes clearer, and if the polls continue to show that a majority now wish to Remain, there ought to be a new referendum which will ask the people whether they still agree to leave the EU, now that it is clear what is entailed. It’s nonsense to say a new referendum would be undemocratic and a device to “change the will of the people”. The will of the people changes regularly. That is why in democracies elections are held at minimum every 4- 5 years.

It is not yet a big margin, but the trend starts to look clear. And this is surely because now, only now, drip, drip, drip, people are working out what leaving the EU will mean for the UK and for them. That in turn shows us that this was never a question that could sensibly be decided by a referendum. Few people understood the issues sufficiently. Only now is it clear that there are several possible forms of Brexit, with many other issues to be negotiated individually. We don’t yet know if the UK will agree to stay within the Single Market and/or the Customs Union. Once that becomes clearer, and if the polls continue to show that a majority now wish to Remain, there ought to be a new referendum which will ask the people whether they still agree to leave the EU, now that it is clear what is entailed. It’s nonsense to say a new referendum would be undemocratic and a device to “change the will of the people”. The will of the people changes regularly. That is why in democracies elections are held at minimum every 4- 5 years.

And what if the will of the people in the new referendum is to reject the idea of leaving the EU? Well you tell me. I didn’t vote for this mess.

In Part 2; What can Czechs learn from this mess?

One comment on “The continuing mess of Brexit, and what Czechs can learn from it (part 1)”