The dramatic billboards that went up on Vítězné náměstí last week, reminding us of the events of that day, caused me to stop and stare at them for quite some time. Of course for Czechs of my age, they can invoke some painful memories that may still be hard to bear. Their lives changed for the worse, their opportunities to develop, learn, travel, limited for years, while I enjoyed those opportunities to the full. But those days made a lasting impact on me too, and created such a lasting interest in this part of Europe, that I eventually made it my home.

Why did I as a 14 year old schoolboy, pay such attention to it? Looking back, there were several things going on in my impressionable head. The school itself played a role. It happened that the history teacher chose to make Modern European history the main part of his curriculum. He was a bit of a bully, but somehow his character fitted the stories that unfolded of terror and repression in Eastern Europe. I have to thank him for that choice, even though at the time I was quite unhappy all round at school. My parents had sent me there because of its educational reputation but it was also a “posh” school, and highly conservative on matters such as how long we could grow our hair. To a 14 year old in 1968, that was a matter of utmost importance.

On top of that, the British government itself was having trouble coping with the Spring of ’68, and the desire of young people everywhere to cast off the restrictions of their parents’ generations. In Britain, pop music was at the heart of this. The Beatles and the Stones had been followed by many more brilliant bands such as my favourites, the Who and the Small Faces. Yet the BBC hardly gave any airtime to this music. it may seem hard for people to believe now, but in Britain, the home of pop culture, the government and the “Establishment” wanted to basically close this culture down.

One result was “pirate” radio stations. They broadcast from ships in the North Sea, in international waters. They played the music we all wanted to hear. All day and most of the night. The British government was so enraged by this, that it started jamming their signals. Yes, they were doing exactly what, according to my history teacher, the Communists were doing to the BBC and Voice of America, in Eastern Europe. All this is the basis for the entertaining film, The Boat that Rocked, which is worth a watch.

So when I watched BBC TV reports of the Prague Spring, I identified with the young people I saw there. They wanted the same things that I and my friends did. Up until then, I had the impression of Eastern Europe under Soviet control as a place that was cold and grey, the people all working in factories. The sight of young Czech people in bars, dancing, smiling, having fun, was uplifting to me.

And so, when the news started to come through on 21 August, I too felt crushed. These people had fought for freedom and had lost. It seemed that we in the West were not going to do anything to help either. Why, my 14 year old self asked, did I grow up watching the USA go to war with Communists in Vietnam but to do nothing while this happens?

I was about to be crushed at a more personal level too. The Sunday following the invasion was a typical August day in suburban London. My parents had their friends visiting; they sat in the garden discussing tennis, growing tomatoes, the price of fish. I was listening intently to BBC radio reports which covered the flickering acts of defiance in Prague. Periodically I rushed out to inform the group of the latest news. I had made the mistake of assuming that because the BBC thought something important, the entire nation would too. Finally when I rushed out with news that an ammunition truck had been blown up in Prague, my Mum put an end to what she thought was an embarrassing distraction from their eldest son. I can still hear her say in front of me, addressing her friends in the most patronising voice possible “he keeps rushing out with these little bits of information”. Now, here, many Czechs around me despair at the research that shows the ignorance of younger people to the events of 1968, but it has always been that way. Your school and your parents shape how interested you are in the world outside. If my fearsome history teacher had not himself been obsessed with Lenin and Stalin, and all they brought upon Europe, I might not be sitting here in Prague now.

My Dad, fortunately was a little different to my Mum. He had encouraged me to read “proper” newspapers and listen to the news, and he seemed to respond to my interest in this. When the Czechs faced the Russians in the ice hockey game months later, he pointed out the significance of it, and we both celebrated the Czech victory. After that, slowly the country disappeared from media view, but I remained permanently interested in what was happening behind the Iron Curtain, and the lives of young people there, and how it must differ from mine. When at 18 a group of us schoolfriends wanted to celebrate by enjoying a foreign holiday before going off to Uni., they accepted my exotic idea to choose not Spain or Majorca, but Yugoslavia. Rabac, in fact. And there I engaged with the local young people who worked in the tourist business, and learnt about the real lives of real people – with very similar interests and hopes for the future. In the late 80s I started travelling again across the Iron Curtain, and watched it crashing down at close quarters. When we sat down for Christmas lunch in 1989, as Romania finally fell, my Dad said “I am glad I lived to see this day”.

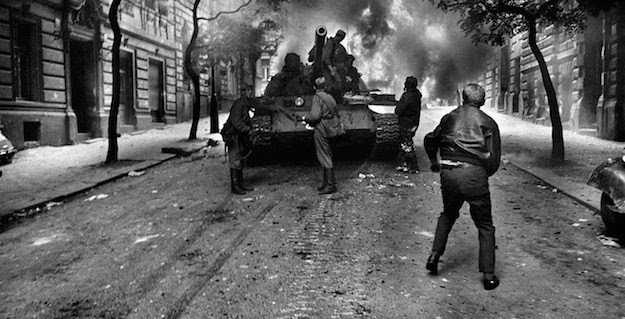

I live and work in Prague 6. I have not been a big fan of the current Mayor, Ondřej Kolař, but in recent months he has asserted himself to remind Russia, (whose embassy is in his area) that Czechs will decide for themselves what statues they will host and how those statues will be presented to citizens. He has received a certain amount of intimidating Russian criticism for this, and has shown himself to be undaunted, launching the impressive outdoor displays which remind people of all that 21. August brought upon the country. I admire him for that. His firm, intelligent approach reminds me of the scenes 50 years ago of Czechs jumping onto the tanks trying to reason with the stone-faced troops.

I live and work in Prague 6. I have not been a big fan of the current Mayor, Ondřej Kolař, but in recent months he has asserted himself to remind Russia, (whose embassy is in his area) that Czechs will decide for themselves what statues they will host and how those statues will be presented to citizens. He has received a certain amount of intimidating Russian criticism for this, and has shown himself to be undaunted, launching the impressive outdoor displays which remind people of all that 21. August brought upon the country. I admire him for that. His firm, intelligent approach reminds me of the scenes 50 years ago of Czechs jumping onto the tanks trying to reason with the stone-faced troops.

And as for me, I think back to 50 years ago, watching the tanks; I never dreamed that I would one day be there, that it would become my home, a normal, open European country – no more and no less than those people on the tanks wished for then. They lost the battle, and suffered for years, but who can argue that in the end they won.

And as for me, I think back to 50 years ago, watching the tanks; I never dreamed that I would one day be there, that it would become my home, a normal, open European country – no more and no less than those people on the tanks wished for then. They lost the battle, and suffered for years, but who can argue that in the end they won.

It’s named “Vítězné náměstí” (“Victory Square”) for a reason.

Photo sources

Lead photo: Ruske tanky-okupace 1968-Praha-CR-komunizmus-rf-hord